Introduction

Imagine living in a place where the sun doesn’t rise or set for half the year and where all the world’s time zones technically meet at a single point. That’s Antarctica, a continent that truly defies the typical rules of time. While most of the world uses time zones based on longitudinal lines—vertical divisions running from the North to the South Pole—Antarctica’s location and extreme climate make a standard time zone system nearly impossible to apply.

With no permanent residents and dozens of international research stations, each set up by different countries, Antarctica has become a patchwork of time zones, each station often following the time zone of its home country. This means that two neighboring research stations can be operating hours apart. This article explores the complex way time is managed in Antarctica, the impacts on daily life, and why this icy continent offers a unique perspective on our relationship with time.

The Geography of Time in Antarctica

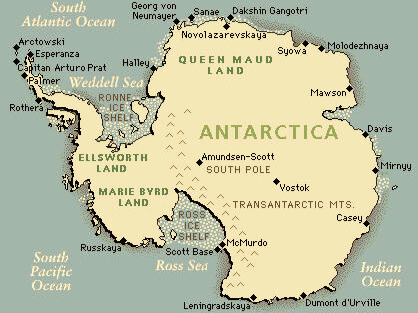

Antarctica’s location at the southernmost point of the Earth means all longitudinal lines converge at the South Pole. This setup theoretically places the South Pole in all time zones at once. However, without permanent residents or regular towns, Antarctica has never established a standard time zone. Instead, it is up to each research station to choose the time zone that suits them best, typically the same as their home country or the country that provides their supplies.

For instance:

- The United States’ McMurdo Station and Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station both use New Zealand time, as their logistics and supply flights come from Christchurch, New Zealand.

- The British Rothera Research Station follows GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) in winter and aligns with British Summer Time in the summer.

- The Australian Mawson Station uses Australian Western Standard Time, as it connects closely with Western Australia.

Each of these time choices reflects practical needs rather than geographical logic, creating a unique patchwork of time zones across Antarctica.

Early Antarctic Explorers and the Need for a Clock

When early explorers arrived in Antarctica, they faced serious challenges, from surviving harsh weather to keeping track of time without a reliable day-night cycle. Early explorers often stuck to the time zones of the places they had left, such as London or New York, as this was easiest for navigation and communication.

As more countries established research stations, each one adopted its own time zone, often to match the logistics from its home country. This setup allowed researchers to plan supplies, communication, and coordination with support teams back home. Today, this practice remains, creating an unusual collection of time zones in Antarctica.

The Role of UTC in Antarctic Coordination

To help unify activities across research stations, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) is often used as a shared time reference. UTC, the same time standard used for global communication and internet servers, serves as a common point of reference. This allows researchers and operations to sync certain tasks or meetings at the same hour, even if they are technically operating on different time zones.

For example, a weather experiment might involve teams at several stations collecting data at the same “UTC” time. Using UTC helps scientists overcome the challenge of working across multiple time zones, simplifying coordination and making global collaborations smoother.

Life on “Antarctic Time”: Coping Without a Normal Day-Night Cycle

One of Antarctica’s most significant challenges is its unusual light cycle: 24-hour daylight in summer and total darkness in winter. This extreme pattern makes it challenging to keep a regular schedule based on natural light. Many people in Antarctica rely on clocks to manage their routines rather than looking outside to see if it’s day or night.

In summer, when the sun never sets, scientists might block their windows to simulate nighttime, helping their bodies stick to a regular sleep schedule. During the dark winter months, they use artificial lighting to keep up a sense of daytime. This constant adjustment can be mentally and physically taxing, as the body’s natural “biological clock” relies on light to maintain healthy circadian rhythms. Without a true day-night cycle, many people experience changes in mood and energy, often feeling “polar insomnia,” or trouble sleeping.

How Different Antarctic Stations Use Different Times

Because each research station follows its own chosen time zone, neighboring stations can have hours of difference between them. Here’s a look at some notable examples:

- McMurdo Station and South Pole Station (United States): Both stations operate on New Zealand time, even though they are nearly on opposite sides of the continent.

- Rothera Research Station (UK): This British station uses GMT and shifts with British Summer Time, making it easier for researchers to communicate with home.

- Mawson Station (Australia): It operates on Australian Western Standard Time, connecting it with Perth, Australia, for smoother communication and logistics.

This lack of a unified time zone means that researchers often have to be flexible when coordinating activities with neighboring stations. The variety of time zones can be confusing, but it allows each station to work smoothly with their home country, making planning and supply deliveries easier.

Health and Mental Challenges of Time Confusion

With its unique conditions, Antarctica can affect both physical and mental health. People rely on clocks, not the sun, to structure their day, which can make it hard to keep a steady routine. Circadian rhythms, the body’s internal “clock,” can become disrupted without regular sunlight, leading to sleep issues, mood swings, and even symptoms similar to jet lag.

To combat these challenges, stations use strategies like:

- Light Therapy: Special lamps that mimic daylight can help boost mood and reset circadian rhythms, especially during the dark winter.

- Social Activities: Regular events and gatherings help create a sense of normalcy and provide breaks from work, which can help maintain mental health.

- Structured Schedules: Sticking to set meal times, work hours, and exercise routines helps people maintain a stable daily rhythm.

These techniques help researchers adjust to a world where time and light don’t always align, but challenges remain.

The Unique Role of Antarctic Tourism and Time Management

Each year, a limited number of tourists visit Antarctica, typically by cruise ship. These cruises often operate on their own set time, usually the time of the departure port or the time chosen by the cruise company. Managing time for tourists is often more straightforward, as cruises keep a set schedule for excursions, meals, and other activities.

For travelers, the unique time-keeping system of Antarctica adds to the surreal experience. Some cruises even celebrate “polar midnight” or “polar noon,” adding to the charm of a trip to the “timeless” continent.

Could a Unified “Antarctica Time” Work?

With its many time zones, some have suggested establishing a unified “Antarctica Time” for the continent, which would make communication and planning easier. However, there are both pros and cons to this idea:

- Pros: A single time zone could simplify coordination, reduce confusion, and make the experience more cohesive for all residents and visitors.

- Cons: Each station relies on its time zone for logistical purposes, and changing to a unified time might complicate things. For instance, New Zealand-time zones make sense for US stations due to supply logistics from Christchurch.

For now, each station continues to follow its own time, based on the needs of the people who work there.

Antarctica as a Training Ground for Space Missions

Interestingly, the time challenges of Antarctica make it a good model for space exploration. In space, day and night are also absent, and astronauts have to rely on Earth-based schedules to maintain routines. The time-keeping experiences in Antarctica, from the use of artificial light to help with circadian rhythms to the mental impacts of isolation and time confusion, offer valuable insights for future Mars or Moon missions.

NASA and other space agencies study these environments to prepare for the time challenges astronauts will face in space, where a day-night cycle doesn’t exist.

Conclusion: The Flexible Nature of Time in Antarctica

In Antarctica, time is more than just a set of hours on a clock; it is a flexible, human-made structure designed to meet the practical needs of those who live and work there. With each station operating in its own time zone, and daily routines determined by schedules rather than sunlight, the continent’s unique relationship with time illustrates the adaptability of human life in extreme conditions. Antarctica, where all time zones meet, is a reminder that time, in the end, is what we make of it.

FAQ: Time Zones in Antarctica – A Unique Challenge

1. Why doesn’t Antarctica have a standard time zone?

Antarctica is located at the South Pole, where all longitudinal lines (which define time zones) converge, technically placing it in all time zones at once. Since there are no permanent residents and the continent is populated by international research stations, each station adopts a time zone based on the needs of the country that operates it, creating a variety of time zones across the continent.

2. What time zones do the different Antarctic research stations use?

Each research station typically follows the time zone of the country that operates it. For example:

- McMurdo Station and Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station (USA) use New Zealand time, as they receive supplies from New Zealand.

- Mawson Station (Australia) follows Australian Western Standard Time.

- Rothera Research Station (UK) uses GMT in winter and aligns with British Summer Time.

3. How do people in Antarctica deal with 24-hour daylight in summer and total darkness in winter?

People in Antarctica rely on clocks rather than sunlight to keep a daily schedule. During the constant daylight of summer, they block windows to simulate nighttime and stick to regular routines. In winter, artificial lighting is used to create a sense of “daytime,” helping people maintain a regular rhythm despite the 24-hour darkness.

4. Does Antarctica use Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)?

Yes, UTC is often used as a common reference across research stations for coordinating international scientific projects and meetings. However, each station still operates on its chosen time zone for everyday activities, with UTC simplifying joint activities across different stations.

5. Why do some people experience sleep issues in Antarctica?

The lack of a natural day-night cycle can disrupt circadian rhythms, or the body’s internal clock, leading to sleep issues and mood changes. This condition, known as “polar insomnia,” is managed with light therapy, structured schedules, and social activities to help residents maintain their mental and physical health.

6. How do tourist cruises manage time in Antarctica?

Antarctic cruises often follow the time zone of their departure port or a time zone chosen by the cruise company, keeping a consistent schedule for excursions and activities. The time-keeping system for tourists is straightforward and adds to the unique experience of visiting this “timeless” continent.

7. Would having a unified “Antarctica Time” help?

A single Antarctica Time could simplify coordination between stations, but each station’s current time zone is chosen for practical reasons, like syncing with supply and communication schedules from home countries. While a unified time might reduce confusion, it could also complicate logistics for individual stations.

8. How is Antarctica a training ground for space exploration?

Antarctica’s extreme conditions and unusual timekeeping challenges make it similar to conditions astronauts face in space, where there is no day-night cycle. Space agencies study Antarctica’s impact on circadian rhythms, mental health, and isolation, which offers insights into what astronauts will experience on long missions to Mars or other planets.